About ten years ago, fresh out of college and about to leap into a science writing program, I was home for the summer and looking around for ways to keep busy. A little sewing school had opened down the street from my folks’ place, and they were offering not only construction classes but pattern drafting. I’d been sewing for years, occasionally copying a pattern from an existing garment or making minor pattern changes like dropping a waistband or reshaping a neckline or skirt. The idea that I could instead create them from the ground up? Revolutionary.

A mere few weeks of workshop later, I was burning with newfound power. Flat drafting on paper isn’t the only way to create sewing patterns, but it clicked into my brain like a game expansion. Start by drawing up a properly fitted sloper or block, which is a pattern shaped exactly like your body that forms the foundation for anything else you might make. Learn a few basic manipulations like adding ease and transforming darts, add collar and sleeve drafts, and you can create nearly any pattern. I was unbound by trends, no longer limited by what the pattern companies thought would sell, free to rip off the designer stuff I couldn’t afford and all the steampunk gear my nerd heart could want. (Yeah, I know, but it was 2010.)

Patternmaking was also a road into good fit, which had eluded me for years. I grew up using commercial patterns, which are a bit like flattened-out ready-to-wear clothes but based on fit standards that have been frozen in time for decades (not that they were ever designed to fit square-shouldered teenage gymnasts). I attempted to make my own jeans once in high school, and was utterly thwarted by bizarre fit problems. But through trial and error, a lot of detailed measurements, and plenty of failed muslins, I gradually learned the shapes that worked for my body. Now they’re so ingrained that I can freehand a crotch curve or sleeve cap from a few reference lines.

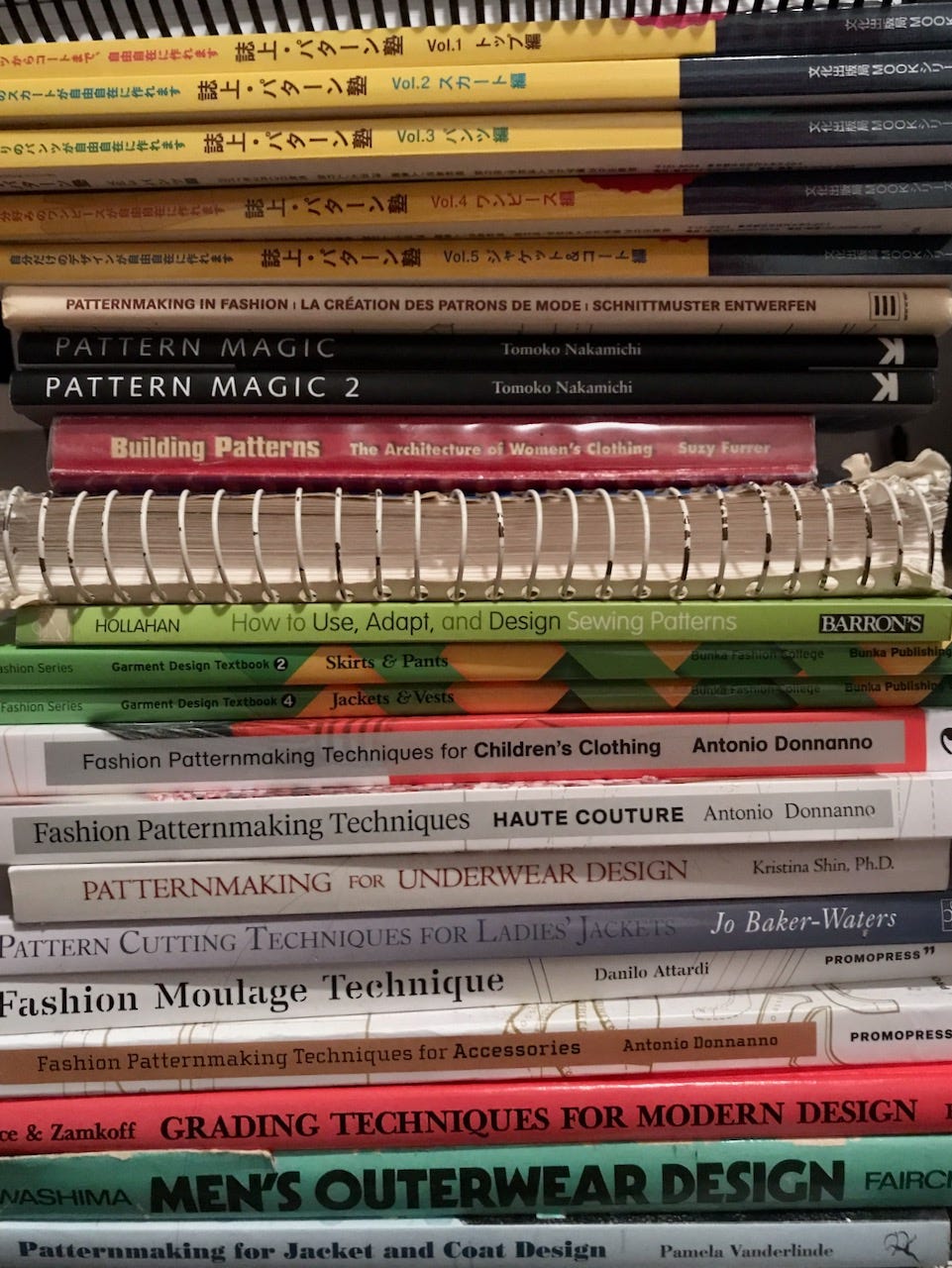

An obsession was born. I collected tools and reference books – the photo above isn’t complete, but a rough approximation of where ten years of library-building has gotten me. I bought rolls of tracing paper and started experimenting, making patterns for pants, dresses, shirts, jackets. I bought commercial patterns and international pattern magazines to study the shapes, building a whole vocabulary of style lines, silhouettes, and proportion.

But also, patterns for everyday clothes could only hold my interest for so long. Real clothing is largely designed by people who went to fashion school, who know where the seams of a garment conventionally go and how they fit together. The kind of patterns that are widely available reflect that, and the pattern pieces are predictable enough that an experienced stitcher can often leap right in without any need for instructions or even labels. Compare that to the joyful anarchy of translating garments that sprang whole from the brain of an artist who’s barely heard of zippers, and you can see how cosplay changes the game for a patternmaking enthusiast. There was something deeply satisfying about puzzling out Ezio’s hood from Assassin’s Creed 2, or Garnet’s weird jumpsuit from FF9.

So, where to start? Assuming you have a basic idea of how to put garments together, nearly any patternmaking textbook will do the job. (If not, a basic sewing book or commercial pattern is a great place to start!) Many of the books I learned from are now out of print, but there are so many others out there that it doesn’t matter much. As long as you find one with a communication style you like, that shows how to draw up a basic block, fit it to your body, and transform it with dart rotations, ease, and detail variations, it should do the job just fine. Most pattern books also contain some number of basic garment drafts, but while they’re useful examples you shouldn’t feel limited to what’s shown in the book. The basic principles are what you’re really after, and the rest is up to practice, experimentation, and learning the proportions that work for your body and your preferences.

Flat drafting systems are always going to be an approximation of a 3D body, and in order to achieve that approximation they’re always going to have some assumptions baked in. Depending on how your personal dimensions interact with these, you may end up with some weirdness in the initial block. A good fitting book should be your next stop, as you troubleshoot the draft and make any alterations necessary to customize it. Really take the time and make the block fit as perfect as you can get it, because any patterns you make from it in the future should inherit this same fit.

Very few patternmaking books also discuss construction (the Bunka Garment Design Textbook series in the picture above are some of the only ones I’ve found) so you need to be able to puzzle out assembly order on your own. This is where it helps to have made garments before, or at least have a good general sewing book at hand. For figuring out the finer points – this needs to be finished before that piece goes on, etc. – nothing beats making a mock-up before you move on to your real fabric. This is a good practice anyway, because sometimes a proportion that looks good on paper lands badly on a 3D body, and sometimes a mistaken measurement or other error leads to a non-obvious flaw in the draft. Any problems or construction challenges you can discover in this test run will save you lots of grief in the final garment, so even a very bad mock-up can be a worthwhile experience. Additionally, you should expect a bit of tinkering on any new pattern to accommodate the specific properties of the fabric you plan to use. Is it a thick, stiff material that makes everything feel tighter than it would in muslin? Is it something floppy and fluid, that wants to sag away from the shape you put it in? In the end, fit is a three-way conversation between the pattern, fabric, and the body inside, and even more so when you get into making patterns for stretch fabrics.

For cosplayers especially, I recommend learning the basics and then checking out some of the patternmaking books that deal with more unusual ideas and transformations, like the Pattern Magic series by Tomoko Nakamichi, Antonio Donnanno’s books on patternmaking for haute couture and accessories, and Stuart Anderson’s Pattern School page for stretch pattern drafting. Since cosplay is so full of odd silhouettes and unusual materials, you want a broad and varied pattern vocabulary in able to accommodate this variety.

Much more recently, I decided I needed to add draping to the repertoire. Lots of people start with this method, and I’d done enough reading to grasp the basic idea, but I didn’t have a dress form that really matched my shape until the end of 2018. Since the entire point of draping is to create patterns directly on a body, it wasn’t very practical before that. When I acquire a new tool though, I go looking for a way to use it.

My longest-term project is the Shaman Empress from Monstress. Basically none of whatever the Empress wears under her robes is visible in the reference materials we’ve seen so far, so I’m making something up based on the available information. Most importantly, the full-length embroidered panel at center front needs to hang from something that isn’t the floaty gathered blouse – ideally a structured bodice or corset with lots of boning to prevent distortion and sagging from the weight. I drew up this paneled bodice with lots of seams wrapping around at weird angles, strongly influenced by Maika’s armor from the Monstress issue 13 cover, which I built back in early 2018 and still love. The neckline is shaped to match the upper edge of the embroidery panel, and will be refined in mockups to play nicely with the blouse underneath as well.

I spent a couple days trying to do the pattern flat, but a major weakness of paper drafting is that every time you change one piece, you need to trace the effects across all the other pieces it touches to ensure that they’ll still match up. I’ve mostly been a flat patterning partisan thus far, but trying to lay out all these curvy seams while preserving fit was not a fun time and after a deeply mediocre first muslin I needed to try something different.

This bodice has been on extreme slow cook (that post was fully a year and a half ago, with only intermittent progress since) but I’m happy with where it’s going, and it’s a nice reminder that if one tool isn’t doing the job, there’s usually something out there that will work better. Learning new skills is always worth it.